Review by Nicholas Hauck

Irreducible to any single literary genre, the Volodinian cosmos is skillfully crafted, fusing elements of science fiction with magical realism and political commentary. There is an ominous lack of tangible reference to our world, the world outside this cosmos, and in refusing to directly reference our so-called reality, including “our” literary traditions, Antoine Volodine consciously accentuates the radical strangeness of his fictional world, highlighting its independence and its incommensurability with traditions, literary or otherwise. According to Volodine, the contemporary world is absolutely unstable and dominated by the absence of all hope; this is the source of the radical otherness saturating his work, an absence-as-source, like a negative without referent. We live in this permanent rift, something, he says, that haunts him and drives him to write, to scream, to create something outside and beyond all this . . .

Review by Joseph Burnett

Much like his fellow American peers Pauline Oliveros and La Monte Young, Charlemagne Palestine has spent much of his career using the languages of minimalism and drone music to trace imaginative realms that frequently outdistance the physical. But his approach is far more abstract than that of his illustrious, better-known contemporaries, and the fact is that there is something palpably unsettling about the current phase of Palestine’s work. The techniques and approaches used are similar or even identical to those employed by Palestine in his early works like Strumming Music (1974) or the all-electronic statements collected on In Mid-Air (1967-70), but these days he delves much deeper into esoteric, even oneiric, territory. And the thing with dreams and enigmas is that they sometimes hide and conceal disturbing revelations . . .

Review by Sophie Hughes

The experience of reading the prize-winning Korean-born writer Bae Suah is simultaneously uncanny, estranging, and spellbinding, an effect that becomes perceptible the more you read. Quotations perhaps give a taste of Bae’s penchant for reiteration, but they do not, cannot show quite how sophisticated her employment of repetition is—ideas and images woven throughout the lengths of these plot-light but carefully constructed stories—or how it gives rise to such an intense reading experience. While the idea that the same words never carry the same weight or meaning twice is not a new one (Gertrude Stein’s ideas on insistence, or Heraclitus’ river theory work along the same lines) Bae exploits it in her fiction to tremendous effect: delighting in the possibility of words having infinite meanings and effects, in these short, spiraling narratives Bae sends her readers around and around the same words and ideas, lifting us to new proximities to them, and to mesmeric landscapes, both geographical (in Korea) and psychological (in her narrators). These voices and set scenes, in particular with the more assured Nowhere to Be Found, resonated with such hyper-real clarity I felt I might have dreamed rather than read them: How long had I been in this book?

Review by Scott Esposito

The overlooked genius among geniuses—this is how people always seem to refer to Silvina Ocampo. As the story goes, she was the ill-fated member of Argentina's great modernist clique, always outshone by her publisher sister, Victoria, her brilliant husband, Adolfo Bioy Casares, and their incandescent friend, Jorge Luis Borges. Borges, Bioy, and Ocampo all brought the surreal into the everyday, but whereas Bioy imagined how technology interfaced with his bizarre plots, and whereas Borges heroicized his adventure tales into master narratives that wrought new truths, Ocampo camouflaged her fantasies, as though they were microscopic details in yards of baroque wallpaper. If you blink at the wrong moment everything will look perfectly normal, yet once you do see that tiny seam in the fabric of what is, your eyes will see nothing else . . .

Review by Heather Cleary

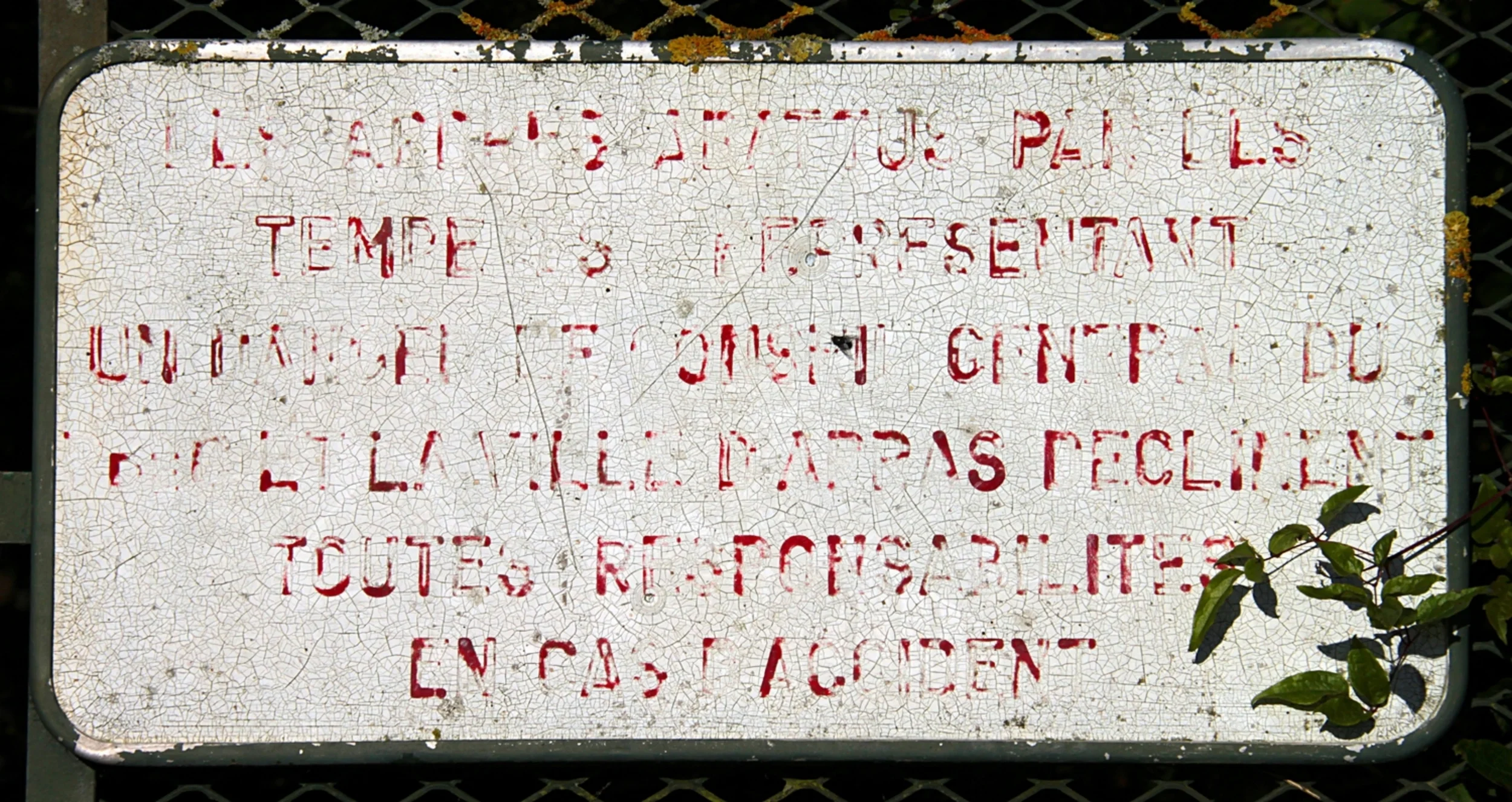

Jacob the Mutant , notwithstanding its buried mises en abyme about the act of writing, positions itself primarily as a work of literary historiography. The book’s opening pages establish this central conceit:

The Border was perhaps one of the least known works of the Austrian writer Joseph Roth. A complete translation has yet to surface, although fragments have shown up, like the lines offered above, in specialty magazines in Paris and on the West Coast of the States. The Stroemfeld publishing house in Frankfurt holds an old edition in its archives that is believed to be complete, while the independent publishing house Kiepenheuer & Witsch has another version that, many hold, is just composed of a series of fragments.

Spoiler alert: though Joseph Roth was indeed published by the two German houses mentioned above, and though he did, in fact, write a text called “Die Grenze” (The Border), the work appeared in 1919 and belonged to Roth’s journalistic production (not surprisingly, transmutation does not figure prominently in the original German text). With Jacob the Mutant, then, Bellatin offers us yet another case study in literary shape shifting—both his own and, retroactively, non-consensually, Roth’s . . .

Review by Liam Cagney

The number π is invoked in a few senses. One is that the work brings together two “sides which have begun to clash” in Codera Puzo’s musical focus: on the one hand, free improv, noise, and drone music; on the other hand, notated, “serious” composition; a duality analogous, Codera Puzo says, to that of the number (which is at once unlimited and constant). But π is also here a metaphor: indicating in the music something constant and concrete yet at the same time transcendental and unknown. And in this sense π acts as a surrogate: a stand-in or space-filler that neutralizes the wild musical territory with a reassuring mark of our proud knowledge.

Review by Adam Z. Levy

Yuri Herrera’s English-language debut, Signs Preceding the End of the World, translated by Lisa Dillman, begins, and ends, quite literally, with a glimpse of the underworld. On her way across town, Makina, a hard-nosed switchboard operator, witnesses a street caving in. It looks like the work of the supernatural, but the town sits above “tunnels bored by five centuries of voracious silver lust,” and sections are prone to sink into the hollows below. An unfortunate man and a dog plummet into darkness, and Makina narrowly avoids getting swallowed up herself. This darkness trails her the rest of the book. It is never clear which shadows are to be trusted, which are in fact, or merely resemble, solid ground. As far as signs go, this one is fairly clear. But it does not precede an ending so much as a beginning . . .

Review by Rosie Clarke

As Pitol weaves together memories, dreams, literary criticism, brief histories of twentieth-century Mexico, and odes to writers he regards as exemplary, The Art of Flight circumnavigates neat categorization. But it resists comparison. It resembles a cloudy gemstone: at once glimmering and opaque, layered and precise . . .

Review by Jennifer Kurdyla

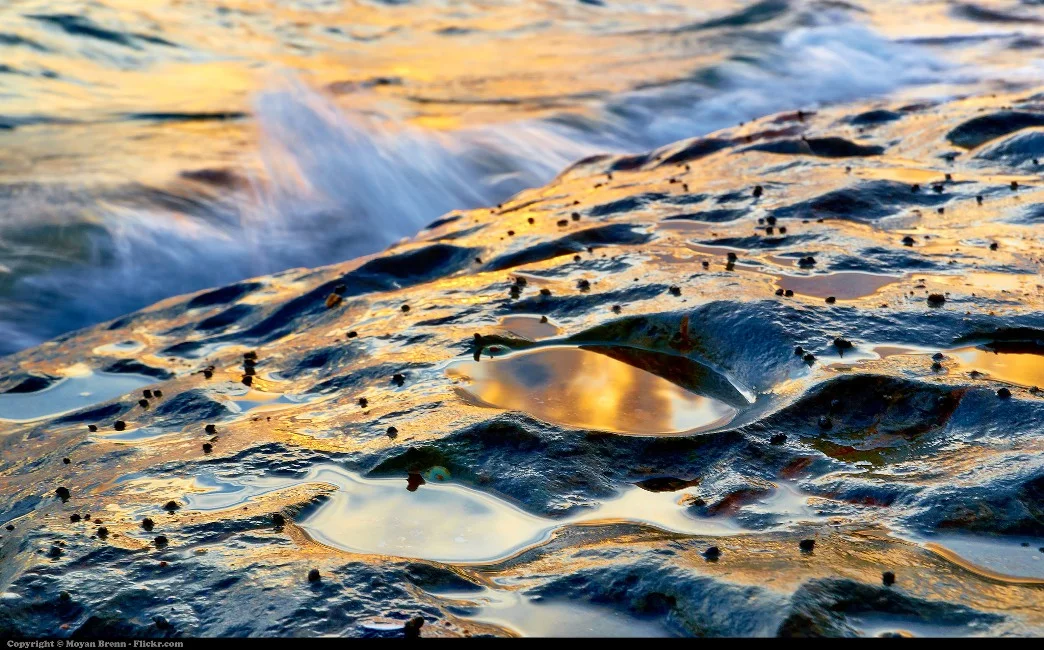

There’s some irony in the way that the largely forgotten French-speaking Swiss writer Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz so wholly and purely embraces pathetic fallacy in his work. Two of his most recently rediscovered publications, the novel Beauty on Earth and the book-length prose poem Riversong of the Rhone, in new translations from Onesuch Press by Michelle Bailat-Jones and Patti Marxsen, respectively, show how Ramuz employs this fluid experimentation with language that was emerging during his day to communicate a oneness between man and his environment. He straddles a line between the old and new on the level of content and form, and in both he strives to convey the eternal quality of existence and, in particular, beauty . . .

Review by Adriana X. Jacobs

The soldiers in S. Yizhar's Khirbet Khizeh remain in a state of waiting that slowly ruins them, as it does the village, all the villages, that they have conquered. This ruin is in the book’s very title, an amalgamation of the Arabic khirbet (“a ruin of”) and the Hebraized Khizah (in Arabic it would be pronounced Khizeh, which the English translation reinstates). The soldiers have become the walking dead, covered in fleas like the dog carcasses rotting beside them, but the text also shows signs of ruin and breakdown in its meandering plot (if this word even applies), sharp transitions, puzzling syntax. S. Yizhar’s prose requires a reader to reassemble sentence order, another way that the distance between reader and speaker collapses, but the stream-of-conscious effects that he employs also lull a reader into a kind of trance and then, suddenly, as for the soldiers, a sudden movement brings the reader back into the text and scrambling to figure out how they got there. In these moments, rereading feels very much synonymous with retracing and rewriting . . .

Review by K. Thomas Kahn

How does one begin to write the history of a woman whose narrative has been submerged, both beneath that of her husband and beneath time itself? How does one set about reconstructing a life from scant fragments, oral histories that carry with them their own subjective—and often biased—versions of the “truth”? Is it even possible to excavate a female artist from obscurity when most artists often inadvertently and unwittingly take part in their own self-erasure? These are some of the questions Nathalie Léger considers in Supplement à la vie de Barbara Loden, her widely-acclaimed and prix-winning 2012 book. Freshly translated by Natasha Lehrer and Cécile Menon as Suite for Barbara Loden, Léger’s Suite raises resonant points about the nature of influence upon artistic creation, the thin and often tenuous line between fiction and reality, and the impossibility of building biographical pictures without a visible (and wholly participant) narrative voice balancing truths and half-truths, all the while applying the lessons learned from sifting through buried archival materials to one’s own experience—what Léger describes aptly as “my dream of a fictional archive” . . .

Review by Ryu Spaeth

The Vegetarian by Han Kang, translated from Korean into English by Deborah Smith, is concerned with the seismic repercussions that follow a seemingly innocuous event: Yeong-Hye’s sudden, mysterious decision to stop eating meat. (Her only explanation: “I had a dream.”) However, if vegetarianism in the West has become as ubiquitous as the Happy Meal, it is a rarity in a country where Spam comes in gaudy gift boxes, nose-to-tail is not a culinary trend but an age-old tradition, and few people outside Buddhist monasteries are concerned with the ethical dilemmas of eating animals. Yeong-Hye, then, is a rebel, if a fairly passive one, and like all outsiders, her alienation serves as a commentary on the community from which she stands apart. But while The Vegetarian certainly relishes its attacks on contemporary Korean society, it is also much more than that, an examination of what happens to a woman who, like Kafka's hunger artist, tries to transcend her appetites—which is to say, the bounds of what it means to be human . . .

Review by Matt Mendez

The title, borrowed from a children’s piece of the same name by Mauricio Kagel, is a play on words: zählen corresponds to “counting,” erzählen “recounting” (in the sense of an account or tale), and when in proximity the two summon up some of the affinities between reiteration and narrativity. Certainly, it comes as no surprise that this tissue of associations resonates with the Germanophile Abrahamsen, whose credo is “music is already music,” that “what one hears is pictures—basically, music is already there.” This is, after all, just another way of saying that writing and rewriting are not so easy to disentangle, that even the most schematic reshuffling of old work brings to bear a mediating sensibility, and that the creation of purely “original” music entails a sort of bricolage in the opposite direction . . .

Review by Craig Epplin

Intimate memories, our bodily relationships with machines, the generational succession of technology, the lure of non-writing, and rhythm as a measure of experience—these concerns wind their way through many of the stories in Alejandro Zambra's My Documents. They are compactly present from the beginning, nested in the opening pages of a memoir-like story titled “My Documents,” is inhabiting the first pages of a collection of the same name. This recursive structure is no accident. Rather, it mimics the nested pattern typical of personal computer files, which can be copied and moved around, which can have shortcuts of the same name, which can be printed out and put together as a book. This is precisely the effect that My Documents seemingly wants to cause: the impression that each individual story forms part of a loosely-conceived totality, held together by proximity as much as by thematic concerns or authorial obsessions. These are just notes, some of the stories seem to say, while others feel more polished. Journal entries, fragments, lists, bad jokes, and regular short stories—Zambra alludes to a number of different genres of writing, yet My Documents still feels cohesively unified . . .

Review by Rodge Glass

The sheer weight of Alasdair Gray’s output in the last decade or so is enough to challenge the attention (and the wallet) of his most ardent supporters. How do you keep up? He switches publishers for almost every publication. He supports the small and the local ones where he can, meaning some of his books go virtually unnoticedGray controls every aspect of each of his projects, the textual and the visual, right down the margins and even the typeface, one of which he has invented himself. It’s overwhelming, sometimes confusing, and—if you pick the wrong book—it can be disappointing. With a writer of this kind, where on earth does someone new to Gray's oeuvre even start? Oddly enough, this retrospective collection of bits and literary bobs, Of Me & Others, is the perfect place. The author suggests it might have been titled A Life in Prose. That would have been appropriate.

Review by Daniela Cascella

Records excite and disturb. Records frustrate and exhilarate. Records call for repetition. Records ruin the landscape: or such is the claim, famously made by John Cage, that gives the title to David Grubbs’s new book. Many musicians operating in 1960s American and European avant-garde and experimental circles shunned such a crucial and controversial element in our perception of music as recorded sound—most notably Cage and Derek Bailey, who stated that their music could only be experienced in full in ephemeral performance settings. And yet many of these musicians allowed their music to be recorded, as evidenced by contemporary releases as well as the numerous archival recordings that would appear decades later, first as CDs and then online. What are the implications of such aural revenants on music practice, on listening and understanding today? And how can the ephemerality of 1960s music performances be compared with another form of ephemerality, represented nowadays by the enormous quantity of audio recordings available online?

Review by Tyler Curtis

Perhaps this is the central concern for Daniel Galera in Blood-Drenched Beard, the economy of symbols, identity, and time. The face, an ever-fluid symbol, has typically been a referent for the subject behind it. For everyone but the protagonist, that particular symbol itself grows roots in one’s mind. But the protagonist’s prosopagnosia makes clear that personhood is just as fluid and tied to the currents of change in time as one’s aging skin. The order and tone of one’s face is commonly transformed into a bodily grammar for the language of the subject, and though it is left fleeting and (visually) unintelligible for our protagonist, he finds himself closer to a more essential unity of the word and the world, how the former in fact constitutes the latter . . .

Review by Tim Rutherford-Johnson

The Anatomy of Disaster (Monadologie IX), written in 2010 by Austrian composer Bernhard Lang, begins like a broken machine. Not one of György Ligeti’s delicately collapsing clockworks or the softly glitching CDs of German electronica group Oval, but a fast, heavy, gunning engine, flailing wildly and dangerously. But not fatally, because the music quickly takes on a chaotic shape of its own. Fragments turn into components. A hiccuping, short–long rhythm metamorphoses into a motif. The thick texture turns out to be comprised of thinner, overlapping layers. And amongst all the dissonances there are sudden glimpses, baffling at first, of the harmonies of a much older language . . .

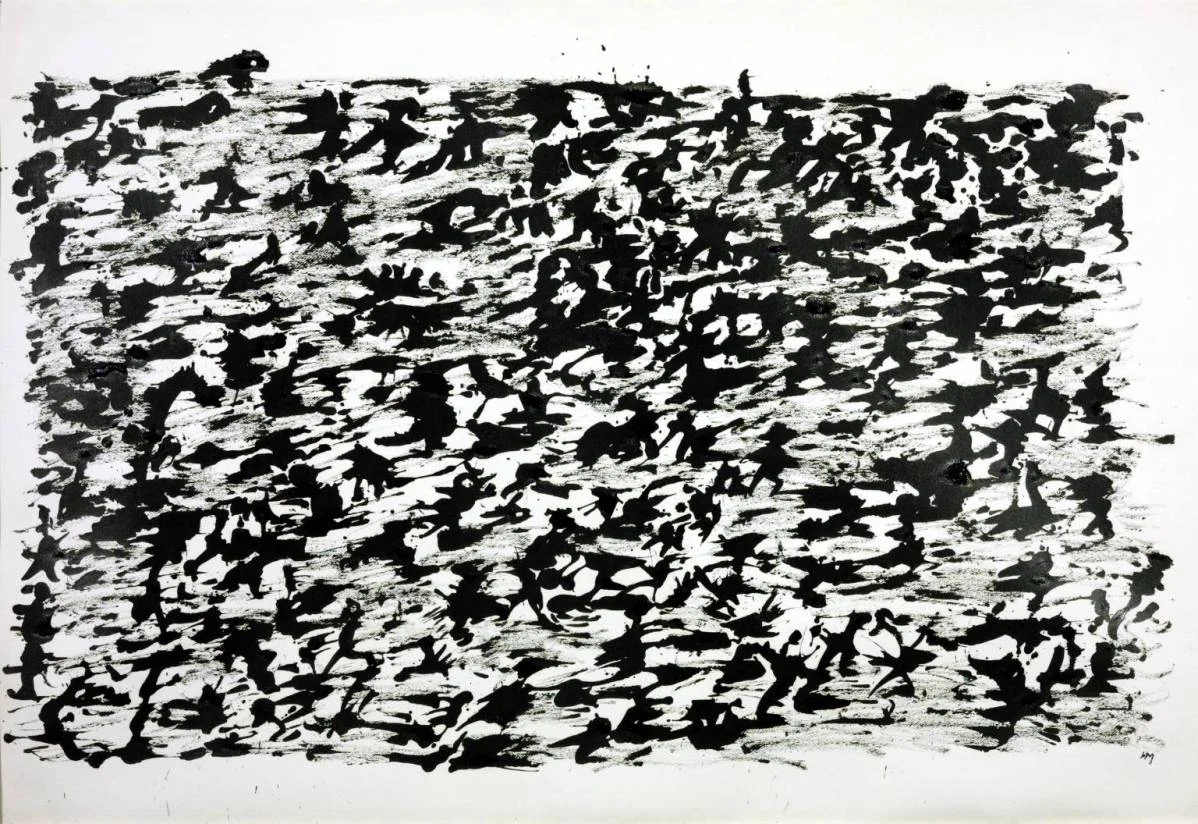

Review by Caite Dolan-Leach

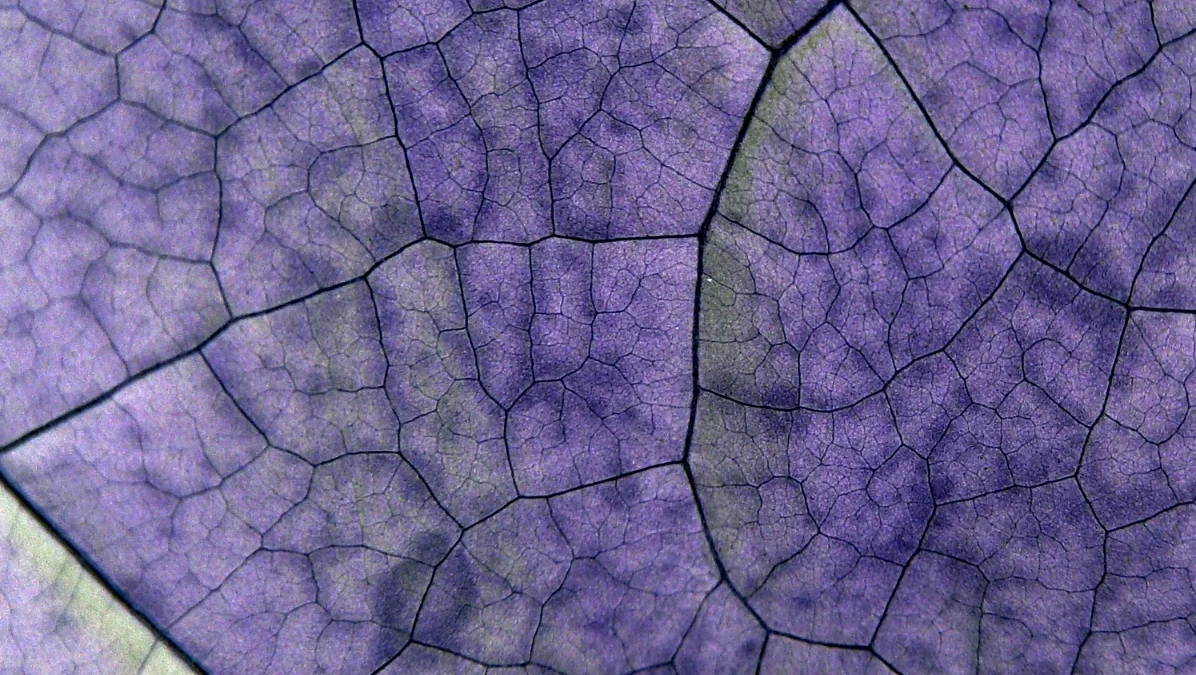

Henri Michaux arrived in Paris in 1924, the same year that André Breton published the First Surrealist Manifesto. Michaux is often mischaracterized as a “Surrealist”; he dabbled a little in the inescapable clan of writers and artists, and certainly shares their concerns about the failures of language and divisions of the self. In the newly translated Thousand Times Broken, a slender volume of poetry, prose and black and white images (exquisitely translated into captivating, strange English by the poet Gillian Conoley) Michaux continues to explore his lifelong fascination and tormented investigation of whether the self can be accessed, whether words or drawings best capture meaning, and whether communication is possible at all. As an artist and writer, he is radically divided, torn and trying to unite all of his conflicting convictions and disparate aesthetic projects . . .

Review by Hilary Plum

It was not until reading Amjad Nasser’s exceptional novel Land of No Rain that I considered just how close the phrase “second person” is to “the double.” In second-person narration, the “you” threaded through the syntax of a novel demands that the reader occupy a life she must pretend is her own. Reading works written in the second person often feels like overhearing someone’s conversation with, or instructions to, herself. In the case of this novel, that premise has been, as it were, doubled: the “you” addressed throughout has, or is, a double. In Nasser’s intricate, mesmerizing prose, we readers become someone we’ve never been, while our protagonist confronts the self he no longer is . . .