This conversation appears as part of a 140-page portfolio of new and newly translated literature on the life's work to date of Kaija Saariaho. Click here for full details on Music & Literature no. 5.

Kaija Saariaho in Paris, 1981. Courtesy Kaija Saariaho.

Clément Mao-Takacs: I would like to start by clearing up a few clichés that seem to have attached themselves to you and your music. To name a few: You’re from Finland, therefore, you love and are inspired by nature; you are “a fiery volcano beneath ice”; since you live primarily in France, you inevitably subscribe to French music. Can we try to make sense of some of these preconceptions? Let’s start with the nature-Finland parallel.

Kaija Saariaho: I think there is some truth to the connection between nature and Finland. The country’s population is so small and nature’s presence there is so pronounced, it’s impossible to lead the kind of urban life you can in a big capital—even though some people try desperately to pretend that they do. Nature is one thing, but what’s more important is light. Changes in sunlight throughout the year are so drastic that they affect everyone. You can’t escape its influence. And because of this experience—which is so physical, we feel it in our body—we, as individuals, have a very special relationship with nature. We have respect for it, we are aware that it’s something larger than us; further, its influence is part of our broader culture and can be found, for instance, in Finnish epic poems, where nature is truly sacred, which was the case for many early cultures. For me, its importance comes from the experience of living in the “period of darkness”—there’s a very specific term for this in Finnish: kaamos—all the while retaining hope that the sunlight will start strengthening again until it is fully restored. Springtime is extremely long, and since the earth has been covered in snow for such an extensive period, there’s a kind of rotting—though pleasant—smell, which gradually gives way to spring vegetation. My relationship to nature isn’t about admiring the aesthetics of a sunset; it’s something much more physical that I carry inside me.

CM-T: I get the impression that you’re interested in light as a phenomenon as well as a source of inspiration. Reading the titles of your works and the indicators you use (luminous, translucent, brilliant, sparkling, bright, etc.)—usually disguised as tempo markings—it feels as though light has a very important place in your imagination, though not in the tone-painting way, as it is in Bach or Wagner, where light is symbolic.

KS: I think that’s just how my mind works. I don’t actually try to find metaphors; they come naturally. It’s true that I’m very sensitive to light and that I’m inspired by it. Sometimes I genuinely do think about orchestra in terms of light. When I picture certain orchestrations, I make instant connections with light. I feel like the senses are mixed together, but I’m not interested in analyzing why or how that may be. What matters most is that it works and that it inspires me. At any rate, for a long time, I’ve believed that the senses are not compartmentalized, but are in fact far more connected than we realize.

CM-T: Interestingly enough, nature and light are elements that are often associated with French music—with Debussy, Grisey, and Messiaen, for instance. And you’ve become connected to French music in several ways: you’ve lived in Paris for many years, you’ve worked at IRCAM (the Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics/Music), your pieces contain some elements connected to the French spectral approach; plus, the affinity between your music and Debussy’s, Ravel’s, and Messiaen’s is so strong that almost every conductor interviewed about your work has pointed it out.

KS: It is interesting how everyone’s said that! Because of course, I very much admire the music of Debussy and Ravel, who are so different from each other. When I was younger, I was really drawn to Debussy because his music is so fluid in form, and yet, so difficult to analyze. His fantastic ear has created things that move me on a very personal level. But he’s not the only composer I love . . .

CM-T: Messiaen, for instance?

KS: Messiaen, of course . . .

CM-T: Your thoughts on Debussy are perhaps a subtler key to this underlying connection, and the same can be said for some of Sibelius’ pieces (beyond your shared nationality). There’s a search for organic solutions where form and material aren’t two distinct elements, but are in fact complementary and inseparable, even from the start of the piece’s creation. In fact, your music cannot be analyzed using classic criteria (many works are neither in sonata nor rondo form, and variational form only appears to a certain extent), since their process is very much metamorphic.

KS: Yes, from the very beginning, my work has sought to unify material and form. I don’t know why, but I feel like I have to reinvent the form for each new piece. The idea of taking a predefined form and saying, “Okay, let’s write a sonata or compose something according to a classical, predefined form”—it’s just not possible with my music. It can’t survive like that; it would be dead before it was even born! Every piece of music must live its own life because each one is utterly its own. Of course, from one work to another, I might come up with similar solutions in form, given that it’s my style. But I either use them consciously, or sometimes I go against my intuition, because I feel like you have to open up the possibilities, try new things. But to come back to material and form, once again it’s like the five senses—for me, there’s a back-and-forth between thought and intuition when composing, which makes it impossible to separate the two.

CM-T: It does sometimes feel like, from one piece to another, you fixate on the same material until you’ve found different forms and solutions for it. This has created a sign of continuity—a kinship—between your works. Is this something that you do consciously?

KS: It’s both conscious and subconscious. I’m completely conscious about reusing a piece of material. When I’m writing a larger piece, I usually feel the need to attack it from different angles, and in some cases go through several revisions. Sometimes it’s simply because I love a work so much that I don’t wish to let it go . . . but this can also be a challenge. I’ll create something with certain material in a certain format and then I’ll try to do something else with it because I feel as though I haven’t explored or realized the material’s full potential. In these instances, I think it’s really interesting to work within limits and constraints. When I reuse material, I set limits on my possibilities, and this can be very inspiring because it forces me to go in new directions. First, there’s whatever comes naturally, then I have to come up with something else.

CM-T: Though in no way repetitive, your music often uses forms of repetition, iteration, rhythmic figure, or reoccurring melodies that create a quasi-ritualistic dimension. Your music is comfortable with what you could call a kind of prayer or incantation—I’m thinking of L’Amour de loin, Château de l’âme, La Passion de Simone. I don’t necessarily mean in a Judeo-Christian way, but in the shamanistic sense.

KS: Yes, that’s true. But I’m not a religious person. For me, music is a study of my own self and of the human spirit. I’ve always believed music to be very deep, or at least it can be very deep. It’s like a liquid that can go into the depths, spread out in all directions, and take on various shapes. Words, on the other hand, are choppy and basic, and the grammar and understanding of sentences can just as easily serve as barriers. Music often speaks much more directly, both to the heart and mind. Certain harmonies are like smells that you recognize instantly. With music, you can have an intellectual perception, but also a sensitive and yet very profound understanding. Feelings and sensations are immediate. I don’t think about all this as I’m composing because it's such a complex and absorbing activity. But through my music, I experience all those things. So I think that if I had a religion, it would be music, because I find it to be so rich, so universal, so profound.

CM-T: You mentioned “words” just now. The human voice is very important to you, especially as a vehicle for texts. The words that you set to voice may come from poems or literature, and are sometimes reorganized (like a collage) . . . Could you say that you have a special fondness for voice as an instrument?

KS: I have such an affinity for the human voice—and a personal predilection for texts! Everything I just said about music can be found in voice, and in an extreme way. In a sense, it’s the richest form of expression because the instrument is inside a human being and there are many things that cannot be falsified when using your voice. Whether or not a work for voice originates from a text, it’s necessarily a different mode of communication than instrumental music. Of course, using a text adds another layer of richness and meaning. I really love using voice, but it was difficult for me to write for it at first, probably because the historical context was difficult. I’ve always loved Berio, for instance, and what he did with voice, but I don’t like music that imitates Berio—and at some point, it felt as though you could only write for voice in that way, you had to write that way. So it took time for me to find a certain freedom and my own way of writing for voice—and to accept it.

CM-T: Your operas and some of your pieces are written in French, though you’ve also used German, English, and Finnish. Which language do you prefer to write in? Or is language simply a tool with its own characteristics?

KS: Yes, it’s a musical tool. Every language is different. I think my pieces are written in the languages that surround me. When I lived in Germany, I automatically gravitated toward German texts. Last year, during my stay in New York, naturally I used texts written in English. When a language is spoken around me, I think I’m influenced—maybe subconsciously—by that environment’s particular sound. What I’m sure of is that each language encourages me to think about the orchestration, the different colors. But I think I’m going to stop writing in French. I’ve already written too much with it. I have to mix things up.

CM-T: Everyone is aware of your interest in poetry, literature, fine arts, and cinematography. However, most people don’t know that you have a diverse range of reading material—that you read Proust as well as scientific journals.

KS: I have to admit that I read Proust in Finnish! It was one of the first translations of Proust published [into Finnish]. That translation was remarkable. Anyway, I didn’t speak French at the time. Now I’ll have to read it again in French to compare the two versions. But you’re right about the diversity of what I read. I enjoy reading in different languages too. When I was little, I read a lot of Russian literature—which was normal at that time. Now I have access to so many books. What I look for above all else are ones with originality and ones that describe human experiences in a smart—but not necessarily formalistic—way.

Kaija Saariaho with with Peter Sellars (left) and Amin Maalouf (right) in Salzburg, 1999. Courtesy Kaija Saariaho.

CM-T: Lots of creative people are introverts who live in their own inner world. Yet, like Mozart and Liszt, you travel a lot, you write about troubled individuals, such as Simone Weil and Émilie du Châtelet, and about painful subjects, including the rape of a young woman in Adriana Mater. What is your relationship with today’s world?

KS: At first, I spent a lot of time living inside my music. When I was little, my inner world was so strong that I couldn’t really leave it. Little by little, I came out of my shell, but what I learned was that the world could be a very hurtful place, and music became a kind of refuge. It was only after becoming a parent that I established a true connection with the real world. It simply forced me to get out of myself. In France, I started living differently because there were all kinds of necessary social relationships. Over time, I started opening myself up, meeting people who weren’t musicians, watching young people play my music . . . So I became more sensitive to the outside world. Maybe I’ve become stronger too. I think I had less of a need to seek refuge in my music and had more and more of a desire to see the world with my music. There are a lot of reasons for this, but one undeniable reason is Peter Sellars, whose artistic credo is to always engage in a dialogue with the contemporary world.

CM-T: People frequently point to the fact that you’re a female composer. I remember a conversation we had in Helsinki in which you told me that, at the time, when speaking French, you preferred to use the word compositrice [as opposed to the masculine compositeur]. Could you tell me a little more about this? Is there something particularly feminine about your process? Because there are indeed elements of your music that stem directly from your experiences as a woman.

KS: Throughout my entire life I’ve had to prove that I am, above all, a composer, and one who is as serious and as smart as any of my male colleagues. My music has been very successful, and I think it’s despite the fact that I’m a woman, while my colleagues have thought it’s clearly because I’m a woman! I've said to myself, “Fine, I’m a woman and I accept the fact that people say I’m a compositrice.” But of course, this term doesn’t work as eloquently in other languages as it does in French. In English, you’d have to say “woman composer,” but you’d never say “man composer.” So I don’t consider myself a compositrice. It’s more of a silly quip that makes people think.

As for my material emerging from my experience as a woman, that's just a point of departure. Once I begin composing, I transform it into pitch and rhythm. So whatever that experience is, it simply becomes an element of my work and not a personal story—that’s all that matters. The material can come from our own lives, the lives around us, or wherever. But at some point, it simply becomes music. That’s why my music is not descriptive. Of course, you can hear the beating hearts of Adriana and the son she is carrying [in Act 1 Scene 3 of Adriana Mater], but more than anything else, it’s a rhythmic issue: how do I vary an unchangeable rhythm, how do I make it not tedious, how do I create a process that will distinguish the child’s heartbeat, how do I make this transformation noticeable—these become questions of a purely technical and musical nature.

CM-T: It’s quite clear that this question of transformation—of a gradual process—is at the center of your studies. In your music, there are often spans that appear to be static on the surface but are actually innerly dynamic due to different variables—textures, for instance. And this metamorphosis occurs slowly, sometimes so slowly that we don’t even notice until it’s over. This was the case, if I’m not mistaken, for your “study” Vers le blanc, and you could almost say it’s a defining trait in your compositions.

KS: Certainly, even if there are more dramatic aspects to my music than there were twenty-five years ago. [Indicates a cup sitting on the table and its shadow on the wooden surface.] I’m definitely always intrigued and interested by the place where the shadow starts and ends. I’ve looked long and hard at it, but in reality, there is no exact spot. At what moment and how does this shadow disappear? It’s as though I’m tempted to see just how far I can go without stopping the movement. It’s connected to our perception of time. A composer—or compositrice—works with time; this assumes a specific awareness of the way in which we manipulate the listener’s ear. And in my temptation to stop time, I have the irrational feeling that, if I succeed, time will become space and I’ll be able to enter a secret realm where I’ve never been before. It’s something along those lines. Once again, the physical parameters are muddled; it’s like a secret invitation to find the celestial pattern that would contain the solution, which I know to be an impossible quest.

CM-T: “You see, my son, time here becomes space.” That’s one of the most famous lines in Parsifal. Connections can be made between your work and Wagner’s, one of which is this interest in sound spatialization, which, with his work, may be hidden (in the orchestra or in Brangäne’s voice) or in motion (the English horn solos in Tannhäuser and Tristan); and in your work, it’s found, for instance, in the chorus in Adriana Mater or in the use of electronics.

KS: I am interested in spatialization, but under the condition that it’s not applied gratuitously. It has to be necessary—in the same way that material and form must be linked together organically. Truthfully, I don’t really like it when musicians move around the room because most of the time it’s unnecessary or distracting. I was really surprised that it worked so well at the end of my clarinet concerto. Actually, what matters most for me is the acoustics of the venue. I don’t know if there’s a connection with Wagner—not an intentional one, at any rate—even though I do love certain works of his.

CM-T: Misterioso is a term that appears regularly in your scores. When Peter Sellars talks about you and your music, he also uses the term mystery. As for me, I’m reminded of paintings by Khnopff, which are so packed with meaning yet remain so mysterious, and so similar to your world. Why the fascination with mystery and the repetitive use of the word misterioso?

KS: Evidently, there’s an aspect of my music that’s mysterious, but when I use the word misterioso, it’s mostly intended as a message for the musicians. I feel like musicians create sound differently when I give the indication misterioso—they’re more focused and involved. In contemporary music, interpretation is often very unemotional and I’ve always wanted to do the opposite, to reawaken the interpreters by inviting their feelings and sensations; that’s why I use words like misterioso, dolce, con violenza, and so on. When I was younger, lots of people teased me for using con ultima violenza, but it was precisely because I wasn’t able to find the level of commitment that I wanted from my musicians.

CM-T: Could you talk about the way in which you compose? I get the impression that, no matter what, you’re at your workspace everyday. Is writing music a daily necessity?

KS: I’m very happy when I write on a daily basis. Of course, so many things are going on in my everyday life that it’s a nearly impossible feat. But that’s my goal. When I’m able to establish this kind of regular work routine, I’m very happy. But in the end, it’s a pretty rare occurrence, and when you mentioned Mozart and Liszt earlier, who worked while traveling, it’s important to point out that they had good reason for doing so—they were also performers who played and conducted their own music. That’s not the case for me. I only travel to attend rehearsals and concerts, which is both frustrating and gratifying. I want to do it, and I have to do it, but every time it means I’m leaving my workspace and interrupting my process.

CM-T: Isn’t it also frustrating because, even for composers who are as successful as yourself, rehearsal time is awfully short and you’re given very little opportunity to provide feedback?

KS: Certainly. Sometimes it feels as though I'm traveling to the other side of the globe to hear Le Sacre du Printemps rehearsed, when I'm in fact attending the world premiere of a work that will only be read two or three times before its performance during the same concert.

CM-T: You've been prolific as a composer, and always have new projects coming up. Can you talk to us about that? How do you envision your future? And what’s your take on your productivity and musical evolution?

KS: I have many projects lined up through 2020. We can never predict what tomorrow has in store for us. I always allow enough time for a project to mature, so that’s why I really like having projects for the somewhat distant future. All of my projects, even the smaller works, have taken time and have required a period of maturation. I don’t look back very often and I’m not interested in arriving at intellectual conclusions about how my music has evolved over the years. It has evolved with me; I’ve had a lot of experiences that changed me and, as a result, my music changed. What’s important to me is to always be writing music in the present while envisioning the future.

CM-T: If you had to define yourself, how would you do it with words and not with music? Who are you, Kaija Saariaho?

That’s a very difficult question . . . I’m someone who has always lived deeply through my feelings, someone with great sensitivity and an inner imagination—especially for music. I’m a composer with a lot of technique and experience, but I feel very humble because I am not a musician or a performer; sometimes, I’m really amazed by the music that’s created from within me . . . In the end, it’s all very misterioso . . .

Still from a video produced by Jean-Baptiste Barrière, projected behind performers during a production of La Passion de Simone. Courtesy Jean-Baptiste Barrière.

CM-T: Could you tell us more about this new chamber version of La Passion de Simone?

KS: I created this new version on the proposal of young artists from La Chambre aux échos. As I was thinking about it, I realized that it was a very good idea, and I was tempted to see how it could work. I had already realized some reductions of my other works, and I knew it could work well. To convert a large orchestra into an ensemble of nineteen musicians means that the piece will be more focused on the individual energy of each musician, because everybody plays an important role, and has to be a very active part of the work.

The best surprise came from the modification of the choir into four individual singers: it was not obvious, but the result was good, especially in this version proposed by La Chambre aux échos, which is a stage version. I do mean “stage version,” but not in an usual operatic treatment: the orchestra was not in the pit, the chorus far at the bottom of the stage, and the solo singer in front of the audience! Everybody was on stage; all of the movements, the gestures, the “action” was led by the music, and even the musicians were sometimes moving on stage, or standing up for a solo. It was very organic.

Another important thing: in the original version, there is an electronic part, which mostly consists in some sentences by Simone Weil, recorded by the French actress Dominique Blanc. It was like a ghost-voice, without body, that summoned the words by Simone Weil and created a kind of balance between the live musicians and singers. But in the chamber version, upon suggestion from the company’s artistic team, I gave up on electronics altogether, so it seemed a natural choice to incorporate a live actress instead of a tape. I was very happy with this solution, which brought more humanity and emotion to the performance. This actress is of course not acting as Simone Weil (neither is the soprano soloist), but one more human presence on stage, a part of this collective ritual between live people addressing their culture and their past.

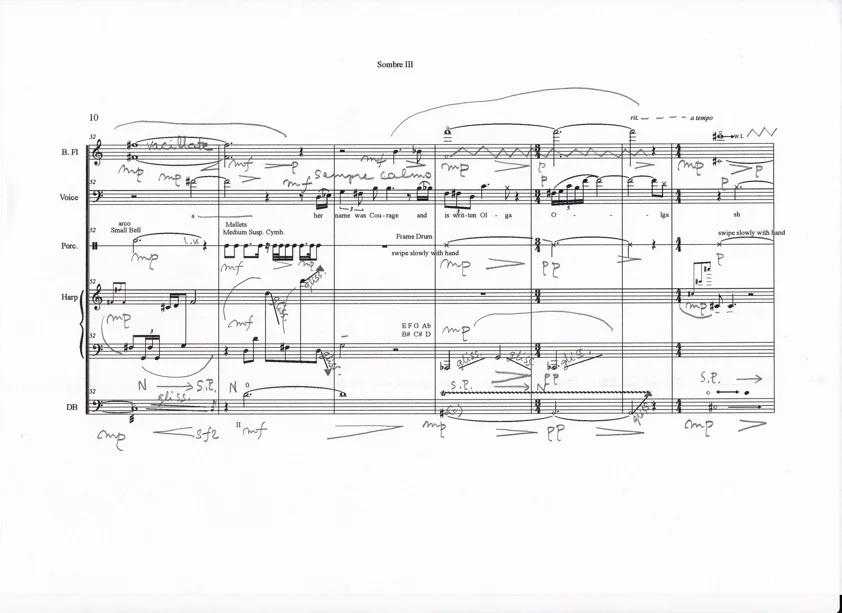

Excerpt from the manuscript of Sombre. Courtesy Kaija Saariaho.

CM-T: You have had a few premieres recently: Sombre (for bass flute, baritone’s voice, percussion, harp, and double bass); Maan varjot (Earth’s Shadow) for organ and orchestra; and you are working on Only the Sound Remains, a musical theater piece inspired by the Noh plays. Let’s discuss these new items in your production, which are—as has been the case so often in the past—inspired by painting or poetry.

KS: When Sarah Rothenberg proposed that I write a piece for the Da Camera ensemble, to be premiered at the Rothko Chapel in Houston, a space entirely dedicated to some of the late works of Mark Rothko—an artist whose catalog I have felt close to for a long time—I immediately began to imagine a dark instrumentation that, I believed, matched the paintings in the chapel. The color of the bass flute sound became a center of this palette; it had in my mind a close connection to Rothko’s work. The title Sombre appeared naturally from the character of the instrumentation, of the texts, and above all, of these last paintings by Mark Rothko. I also wanted to include a baritone voice in the ensemble and began to look for texts.

During my residency at Carnegie Hall, I read more English and American poetry, and there I came across Ezra Pound’s final Cantos, or, more precisely, fragments of them. Their minimal form as well as their heartbreaking content seemed to suit this piece perfectly, and the language (English) helped me to renew my vocal conventions: I was able to explore new paths in my vocal writing.

CM-T: Your new lyrical project, Only the Sound Remains, is also based on texts translated and adapted by Ezra Pound.

KS: As usual, one thing often leads to another. Soon after reading Ezra Pound’s poems and adapting them, Peter Sellars proposed a work on two classical Noh plays adapted by Pound in collaboration with the translator Ernest Fenollosa.

My creation of a version of La Passion de Simone for chamber orchestra also influenced this new project, because it consists of a vocal ensemble of four voices, instrumentation for only seven instruments, and electronics. The main character will be a countertenor, and we will collaborate with the French singer Philippe Jaroussky. I already finished the first part of this work—"Tsunemasa.” This project is co-commissioned by three Opera Houses—Amsterdam, Paris, and Toronto.

CM-T: In fact, in the same way English language renewed your vocal writing, using the bass flute renewed your approach to the flute, an instrument you know quite well, and for which you had already composed so many pieces—most notably, a concerto. Perhaps you've entered a new period, with new colors suggested by new instruments, such as the bass flute (Sombre), organ (Maan varjot), and the kantele (Only the Sound Remains).

KS: Sombre is not a concerto, but rather a chamber music piece with a very important solo part for bass flute, which is an instrument rich in effects. I felt I was breaking new limits of my own world with this piece. Also, I have been wanting to explore the bass flute more deeply for a long time with Camilla Hoitenga, for whom it was written.

With Maan varjot, which is, once again in my opinion, more a work with a prominent solo organ part than a concerto, I was pleased to write for organ, because it has long been an important instrument for me. I enjoy listening to the organ—the repertoire of organ music is so extensive, from Bach to the present—because it was my instrument before I became a full-time composition student. I felt very comfortable, since you could play it and still remain hidden to the audience! My relation to this instrument can also explain the use of a Finnish title for the work.

But despite my intimate relationship to and affection for it, I haven’t written much music for organ. For Maan varjot, I was attracted by its richness, its polyphonic tradition. Organ is a powerful instrument (from ppppp to fffff). I like its ability to produce rich and very precise textures that are in turn controlled by a single musician. I also like its long sustained notes, which are free of the constraints of breathing or the length of a bow. Registration is also a kind of orchestration; you can obtain so many various colors and mix them with the orchestras. The organ part in this work is very graphic, and as every organ is different, the part sounds different with every performance. To realize the registrations with Olivier Latry, who has performed the organ part so far, has been greatly inspiring. I learn enormously from the musicians I collaborate with!

As for kantele, it’s rather different: it’s a traditional Finnish instrument, and many contemporary composers have written for it, searching for new manners of playing, mixing it with electronics . . . but I had never wrote for kantele before. Two things led me to include it in the ensemble for Only the Sound Remains. In my third opera, Émilie, I added a harpsichord to the ensemble and it brought a special flavor to the identity and instrumental colors of the work. It was inspiring to use it with amplification and electronics. So I wanted to continue this experience with kantele, to explore it more extensively. Also, kantele may be considered a Finnish version of the Japanese koto. Last summer in Finland I started to work on the instrument with a prominent kantele artist, Eija Kankaanranta. She will also perform the part in the opera. Of course, the sound is fragile, but that's precisely a part of the beauty and charm of the instrument.

CM-T: You've spent some long periods in recent years in the United States, particularly in New York City. Has the spirit of that city changed anything in your music?

KS: Changing cultures can affect my work in a good way, and I feel that the time spent in New York has done so. Having lived most of the second part of my life in Paris, I enjoyed the welcoming spirit in New York. For example, even after all these years in France people start speaking English to me, as if to emphasize the fact that I am a foreigner or a second degree citizen, or that they do not understand my French—and perhaps they don’t, since I have an accent . . . But in New York, because the city has always been a melting pot of emigrants, there are so many people speaking with different accents that it is not important. People are more focused on communicating, and you're not considered an outsider simply because of your origins. Sometimes, I come to think that the spirit of openness and richness of culture I experienced in Paris at the beginning of the eighties is now to be found in New York.

Translated from the French by Sophie Weiner.

Kaija Saariaho is a Finnish composer internationally known and recognized for her works involving electronics. Her music has been commissioned and performed by leading ensembles worldwide.

Clément Mao-Takacs is a French conductor, pianist, and composer. He is the founding artistic and musical director of the Secession Orchestra and, with Aleksi Barriere, is the co-founder of the music theater collective La Chambre aux échos.

Sophie Weiner is a translator from Baltimore. She has contributed to publications dedicated to art, literature, cinema, and fashion.

Banner image: Kaija Saariaho in 1987. Courtesy of Kaija Saariaho.